January 24, 2026

Screen Time, Blue Light, and Dopamine at Night: What You Need to Know

Mindful Team

Can't sleep after scrolling? Learn how blue light and sleep interact, why melatonin drops, and simple screen-time fixes to improve sleep quality tonight.

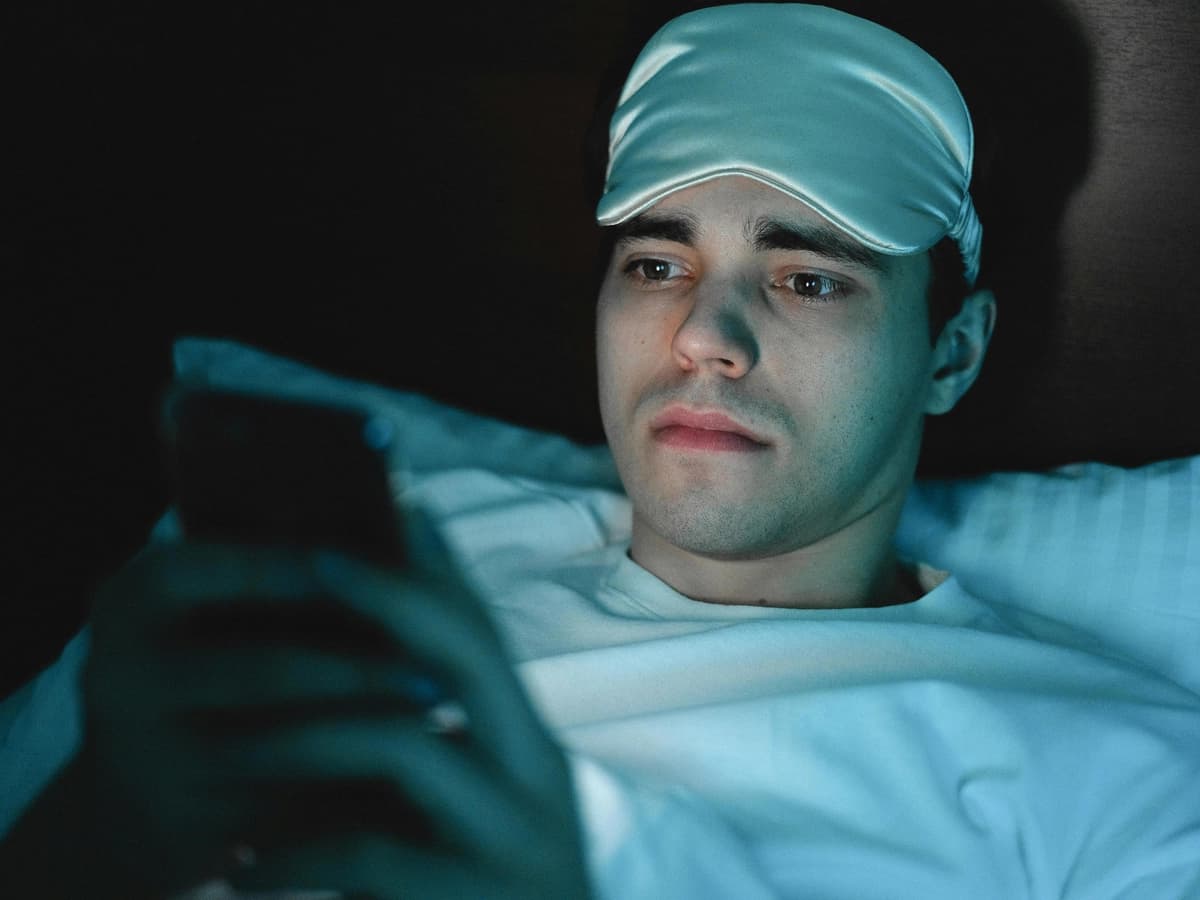

At night, most of us stay in bed and scroll through our phones, watch videos, or check our messages. You only meant to look at one thing, but hours turn into minutes. Your mind is still sharp even though your body is tired. It's not a matter of willpower, but your devices trigger biological responses that prevent sleep.

What Blue Light Does to Your Body

Light serves two purposes: it helps you see, and it controls when you feel awake or sleepy.

Blue Light During the Day is Helpful

The sun produces many colors of light that mix together to create white light. Blue light has short, high-energy waves. During daylight hours, the sun sends blue light to your eyes, which:

- Boosts your alertness

- Improves your reaction time

- Elevates your mood

- Tells your body to stay awake and active

This natural blue light exposure is healthy and necessary.

Blue Light at Night is Problematic

Light Emitting Diode (LED) technology is used in your phone, computer, laptop, and LED TV. The blue light from these screens comes out in short bursts that are much more focused than the light from the sun.

This is a problem at night because your eyes still get "daytime" messages even at midnight, and your body gets confused about what time it really is.

The main point is clear: blue light is present during the day and keeps you awake. Modern screens bring this powerful signal into your evening hours, when you're naturally getting ready for sleep.

How Blue Light Blocks Your Sleep

When high-energy light hits the eye late at night, it changes hormones that make it harder to fall asleep. The pineal gland and the melatonin it produces are at the center of the main process. Melanin is sometimes called the "hormone of darkness," but it doesn't make you sleepy like a sedative does. Instead, it tells the body that it is nighttime, which lowers the body's temperature and gets the systems ready for rest. Darkness triggers its release, while light acts as a brake.

Melatonin Gets Suppressed

Research shows that exposure to blue light in the hours before bedtime suppresses melatonin production more powerfully than other wavelengths. Harvard researchers found that reading a light-emitting e-book for four hours before bed reduced melatonin secretion by over 50% compared to reading a printed book. The brain receives the message to stay alert, preventing the onset of drowsiness.

Your Internal Clock Shifts Backward

Beyond immediate suppression, evening light shifts the body's internal clock, or circadian rhythm. Exposure to bright screens late at night pushes this clock backward. The body begins to believe that 11:00 PM is actually much earlier. This shift makes falling asleep difficult and results in significant grogginess the next morning, as the biological clock hasn't yet signaled "wake up" during the alarm rings.

Children Face Higher Risks

Younger eyes are clearer and filter less light than adult eyes. Children and adolescents are significantly more vulnerable to these effects. Studies show that children exposed to bright light in the evening experience nearly double the melatonin suppression of adults. This makes evening screen time particularly disruptive for school-aged children who need deep rest for development.

Sleep Quality Drops

The quality of sleep suffers alongside the quantity. Users of light-emitting devices often experience less Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep, the stage associated with dreaming and memory consolidation. Waking up feeling unrefreshed often stems from this reduction in sleep architecture quality, even if the total hours in bed seem sufficient.

By blocking melatonin and shifting the internal clock, evening screen exposure fundamentally alters both the timing and quality of sleep, affecting adults and children alike.

Screen Content and the Dopamine Loop

While light keeps the body awake, screen content keeps the mind engaged. This psychological component creates a chemical loop that makes putting the device away incredibly difficult.

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter often associated with pleasure, but in the context of screen use, it drives seeking and anticipation. It powers the "hunt" for information or social validation. Swiping to refresh a feed or checking a notification makes the brain anticipate a reward. This mechanism keeps users engaged because the outcome is unpredictable, as sometimes the content is boring, and sometimes it's exciting.

Apps Engineer Endless Engagement

Applications and games are engineered to exploit this system. Features like "infinite scroll" and autoplaying videos remove stopping cues, creating a frictionless experience that encourages continuous consumption. Every new post or message provides a micro-dose of dopamine. The brain quickly learns that the device is a reliable source of this stimulation. At night, resisting this chemical pull becomes exhausting. The desire to see "just one more thing" overrides the body's fatigue signals.

Active Screens vs. Passive Watching

Not all screen time impacts the brain equally. Passive consumption, such as watching a movie on a TV across the room, requires less cognitive effort. Interactive activities, like gaming, texting, or social media scrolling, demand constant input and decision-making. This active engagement causes cognitive hyperarousal. The brain remains in a state of high alert, processing information and reacting to stimuli. This mental activation delays the transition to sleep even more than the light exposure alone.

Stealing Back Personal Time

For many, late-night scrolling serves as a psychological coping mechanism. Individuals who feel they lack control over their daytime hours often refuse to sleep early to regain a sense of freedom. This phenomenon, called "revenge bedtime procrastination," uses screen time as a way to steal back personal time. The dopamine release from entertainment provides a temporary mood lift after a stressful day, creating a cycle where emotional needs conflict with physical needs for rest.

When cognitive arousal and unpredictable rewards come together, they trigger the brain's seeking systems. This makes users less sleepy and locks them into a cycle of late-night usage.

4 Simple Changes to Reclaim Your Sleep

Implementing strategic boundaries can improve sleep quality without abandoning technology entirely. The goal is to create a buffer zone between high-stimulation world of the day and nighttime rest. Addressing both eye and brain stimulation can significantly improve sleep onset and quality.

Stop Using Screens 1-2 Hours Before Bed

Putting away screens before sleep lets melatonin rise naturally and stops the dopamine cycle. Charge your devices in another room, like the kitchen. This removes the urge to check them during the night.

Turn Your Screen to Black and White

Changing your screen to grayscale makes it less visually appealing. This reduces the dopamine reward, making your phone less tempting. Find this option in your phone's "Accessibility" or "Vision" settings under color filters.

Wear Blue Light Blocking Glasses

Amber-colored glasses physically block the light wavelengths that stop melatonin production. Put them on 2-3 hours before bedtime if you need to use screens. Pick glasses that wrap around slightly to block light from the sides.

Pick Calm Activities Over Interactive Ones

Social media scrolling and gaming keep your brain highly active. Switch to calmer options that require less mental effort. Try an e-reader with a warm light setting, or listen to audiobooks and podcasts instead of scrolling feeds.

Small, regular changes to your evening routine can stop technology from overstimulating you. These adjustments help your body understand that the day has finished and it's time to rest.

Protect Your Sleep in a Digital World

Our bodies evolved to use light as a wake-up signal, but now we live surrounded by screens and constant information. Blue light blocks melatonin while stimulating content triggers dopamine. Together, they create serious sleep problems. Learning how this works helps you make smarter choices. Your devices should serve you, not control your sleep.

FAQs

Q1: Does "Night Mode" or "Night Shift" really help you sleep?

The screen gives off less blue light with these settings, which is helpful, but they're not a full fix. Even though they block most blue light, the screen's brightness and stimulating content can still stop melatonin from working and keep the brain awake. It's also important to lower the brightness and distance.

Q2: Are children really more sensitive to screens than adults?

Yes. More light can reach the retina because children's pupils are bigger and their lenses are clearer than adults'. Studies show that evening light can lower melatonin levels in kids almost twice as much as it does in adults. This is why setting strict screen limits is so important for their growth.

Q3: How long does it take for melatonin levels to get back to normal after screen use?

Melatonin suppression doesn't last forever. Levels usually start to rise again in one to two hours after going into a dark environment. The shift in your circadian clock (the phase delay) can last for a long time, making it harder to wake up the next morning even if you do fall asleep.

Q4: Does reading on a tablet feel the same as reading a real book?

Not at all. Researchers who compared e-readers and printed books found that people who read on light-emitting screens took longer to fall asleep, had less melatonin in their bodies, and felt less awake the next morning. If you like to read digitally, an e-ink device without a backlight or a real book is better for your sleep.

Written by

Mindful Team